2001: A Space Odyssey: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For April 3rd, we are going to have a look at 2001: A Space Odyssey

We are aware of Stanley Kubrick’s perfectionist tendencies now, and there wasn’t really a point in his career where he wasn’t wanting to be fully in charge of his craft. Spartacus is an anomaly of a film that feels the least Kubrickian work in his canon: it’s more of a Kirk Douglas, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Lewis and Kubrick mutt. Point is that the tension being Spartacus is louder than the film’s legacy in some circles. Everything else from The Killing onwards is clearly a part of his filmography. However, the insurmountable strides he took to make each and every film feel like a unique experience wasn’t found in all of his films. Between his debut Fear and Desire and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Kubrick pumped out projects every couple of years or so. The longest gap —at first— was between Dr. Strangelove and its followup 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This was the film. This is when it all changed. This is the moment in Kubrick’s career when his perfectionism became a possessive force that would dominate his works for the rest of his life. This is where the Kubrick we know now truly began. You think of the richest of visuals (not that his earlier works weren’t well shot; he was a photographer first, after all), and you need not look further than 2001. This was cinematic art that was art before it was cinema, and that’s strangely something Kubrick became synonymous with later on, especially with Barry Lyndon, Eyes Wide Shut, and even — to some extent — A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. Dr. Strangelove, The Killing, and Paths of Glory are all conventional enough works that happen to be gorgeous films. Kubrick from 2001 on demanded to push boundaries further than ever before. It’s no wonder that 2001 was more than a new path for him: it was a new way of life for cinema from that moment on.

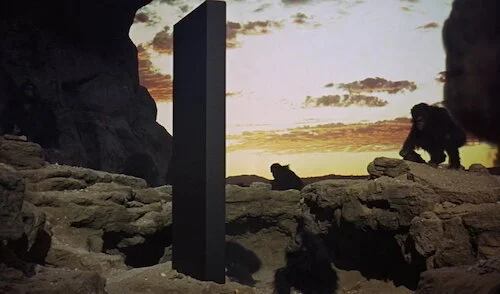

The Dawn of Man.

The film was meant to be a spectacle more than a story, which film academics have largely ignored for over fifty years since (blame people like me). It’s impossible to not find a deeper meaning here, though. Unlike most Kubrick films, 2001 wasn’t an adaptation of any source material. Rather, author Arthur C. Clarke — whom also worked on the screenplay — wrote a novel in conjunction with the film, which was released shortly afterwards. So, see? There is context to some degree. However, Kubrick’s own visions remained intact just how he wanted them, no matter how incomprehensible they may be. It took me at least three watches before I came up with my own (loose) conclusion of how I understand the film on a narrative level. Even then, I’d argue no ones theory will absolutely match anyone else’s.

Part of the appeal — and the difficulty — is how the film’s three parts follow completely different narrative formats. `The “Dawn of Man” opening act is a non-verbal look at primitive hominids creating tools and practices (as well as the all-encompassing monolith that overtakes the entire film). The second portion (and the first to take place outside of Earth) is the most straight forward portion of the film. Humanity has discovered space travel, and a mission to Jupiter is going disastrously wrong when a supercomputer — the HAL 9000 — begins turning on the scientists aboard the vessel. The final act is an experimental freakout, largely due to the entrance of Jupiter’s atmosphere. There is no conventional linearity from here on out. So, you spend one third of the film analyzing every single move of apes, the second third sitting back and allowing the story to develop, and the final third having the rug pulled from you completely.

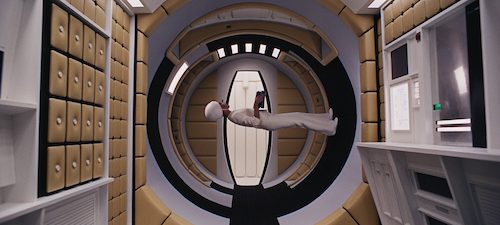

A hostess operating in zero gravity with velcro shoes.

It’s usually by the “Star Gate” sequence that audiences begin to lose the purpose of the film entirely. For me, 2001 is the gift and curse of the progress of humanity. In the “Dawn of Man”, a bone is turned into a weapon. This new tool can bludgeon other primates to assert dominance of a territory or food. It can also be used to hunt for food. There’s an evil attached to this, though: the ability to kill. No matter how much we advance, we are still tethered to our primal roots. This invention can be linked to the monolith that visits Earth, of which the hominids worship. They know as much about the monolith as we do: nothing. Did another species invent this device? Is it a natural creation? Is it just how humans can piece together something much greater? Who knows. We’re in awe of this black plank as much as anyone else in the film is, because Kubrick and friends never give us a clear answer. That’s where the mystique begins, much to the chagrin of those that love digestible films.

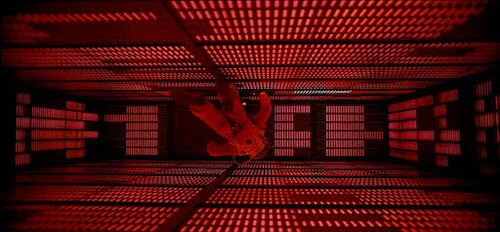

The second act involves humans in space. We don’t need to progress through all of civilized history to know how we get to the future. We know what weapons we’ve made and used since, amongst the other tools and advancements we’ve had. When 2001 was made, the concept of a computer (of this sort) was still a relatively new idea, so the notion that the HAL 9000 could be in its primitive form, despite being a super intelligent machine, isn’t farfetched. It responds in the same way that the apes at the start of the film does: murder works as a form of problem solving. By then, the humans are well past these resorts. They have their tablets, video calling, and other inventions to get by (many, of which, we have in some sort of capacity in 2020). We’re still seeing new frontiers and technologies get consumed by the inherent methods of survival, before a creed or set of laws can take place to fine tune these discoveries.

The inside of HAL 9000.

Unfortunately, the response to HAL 9000’s spree is “an eye for an eye”. Its realization of what death is on a “personal” level is heartbreaking. It tries to express its fears, and then its surrendering comfort into the never ending void ahead (once it is reset to factory settings; it’s a clever metaphor that allows the HAL 9000 to be at its most vulnerable state). Dr. Bowman — arguably the main character in this broken-up story — surrenders himself to the monolith upon the arrival on Jupiter. Like the monolith itself, it’s too much for a human brain to comprehend. Flying vortexes of colours. Shifting landscapes. The passage of time in an unfamiliar form. From there on out, we’re well past our own capabilities, and Bowman acts as a sacrifice to get there. Still, the concept of biological creatures furthering themselves with technology much to the betterment and detriment of their own race still remains. Does this help Earth in any way at this point? I’d argue no, since Bowman’s life restarts, much like Hal’s did. We understand life that heads in one direction, and we are willing to understand Bowman and Hal’s fates as cyclical. We are not ready for the monolith’s full capabilities, never mind what Jupiter has to offer.

To keep even these challenging moments interesting, 2001 boasts the greatest visual artistry known to cinema. Between its breathtaking cinematography (by the legendary Geoffrey Unsworth) and the revolutionary visual effects have rendered the film at least a must-see. Wether this is your forte or not, it’s mandatory to soak in this film at least as an experience. The Star Gate sequence remains an insurmountable cinematic moment that will blow you away every time you see it. That first time you witness it, though, will be a moment you will never forget: where you were, how you were watching the film, or who you watched it with. Kubrick’s adoration of classical music speaks for the film when there is no dialogue to go around; Richard Strauss’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” will always be attached to this film, no matter what. There isn’t any music whenever characters are granted the ability to speak, so we get one or the other: exposition, or composition.

The Star Gate sequence.

As focused on archaic behaviours as 2001 is, it’s still driven by futuristic brilliance. That’s the yin-and-yang relationship found at the heart of this science fiction opus, of which may never be overthrown. As far ahead as we can go as a species, we will forever somehow still be backwards. We are only animals of our own kind. As much progress as we can make, we still have primitive tendencies. No one is smarter or better for understanding 2001: A Space Odyssey. Those that don’t are taken for an exquisite ride. Those that do may leave feeling a little chillier, perhaps because the inevitabilities of our race’s shortcomings were exposed in as few words as possible. Stanley Kubrick himself was exactly like his own opus here. He knew what he could achieve, and burned bridges and made himself, and others, sick to get this result. His reputation is as notorious as it is celebrated. What an end result we got, though. Arguably one of cinema’s heightened examples of stunning art, 2001 remains a peak moment of Kubrick’s career, ‘60s filmmaking, science fiction, and film as an art form on any level. It is as blatantly magnificent as it is thought provoking.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.