Andrei Rublev: On-This-Day Thursday

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

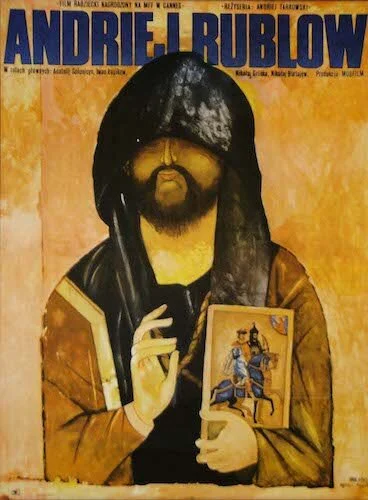

For December 16th, we are going to have a look at Andrei Rublev.

Religious cinema can sound like a turn off to people for different reasons. On one hand, you have nonbelievers that want nothing to do with a preachy picture that might make them feel inferior to those the film was intended for. On the other hand, you have the faithful who might not like the idea of artistic liberty, which could contradict with the beliefs they have. It’s difficult to know what you’re going to get, especially since religion is a personal connection one has with their interpretations of life, death, and the unknown. No one wants their own confirmation of their existence to be targeted. Film itself can serve many purposes: an escape, a discussion, or an understanding. Tossing something as debatable as religion into this mold just doesn’t sit well with many. Still, a number of directors want to share what gives them life, and I can’t blame them.

Andrei Tarkovsky had always dabbled with religious connotations throughout his filmography. He was a Russian Orthodox Christian, who held his spirituality up high for the world to see at every time. He still stepped outside of his comfort zones often, but he used every opportunity to try and pass around the beauty he found in life, and it happened to stem from his affiliations with religion. Keeping what I said earlier in mind, a number of artists have managed to include their Christian faith in their art without being heavy handed, alienating, or pretentious. These include Sufjan Stevens, Terrence Malick, and, oddly enough, members of Slayer (who promoted quite the opposite, actually, so that’s a form of sharing, I suppose). Tarkovsky, to me, was the perfect middle ground: his art was identifiably spiritual, but absolutely anyone could attach to these images in their own personal ways. He found the ideal compromise between scripture and interpretation, and it’s a little bit more obvious than you might think: he simply used the spaces in between.

Andrei Rublev boasts incredible imagery, both metaphorical and photographical.

Andrei Rublev is unquestionably Tarkovsky’s most religious film, and that’s why I’ve spent so much time bringing his faith up. This was the only instance where his knowledge of Russian christianity was used for an entire feature, and not as elements to compliment a whole (the existential dread of The Sacrifice, or the solace in death with Mirror, amongst other cases). Again, Tarkovsky loved utilizing the spaces in between anything: subjects and surroundings, plot points, the screen and the viewer, and God and a believer. He loved the results of causation, as opposed to what creates these results themselves. Case in point: Andrei Rublev is about the titular iconographer, and you never see him paint. At all. This isn’t that kind of a biographical picture. Tarkovsky knows what tribulations he himself has had to face, and how it has strengthened his visions as a believer and as an artist. He utilized film the same way Rublev would take a piece of wood and turn it into an icon of a Christian figure. Icons capture moments in time, including figures in movement and the reactions to said movements in the same image; an entire story is told through minimalist efforts.

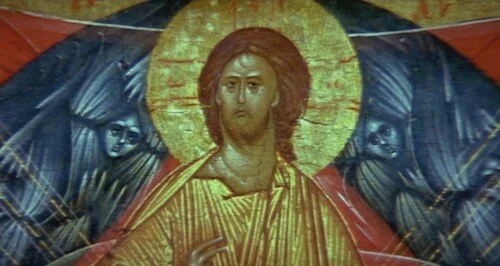

Instead of going for a life story, Tarkovsky renders Rublev’s being as a series of parables, as if his odyssey was its own scripture. Portions of his life are turned into vignettes, either explicitly or with enough metaphorical presence to feel like a tale of morality. For instance, the opening sequence featuring the hot air balloon trip that is stunted by mass hysteria, is clearly imagery being placed beside real life; this includes a horse rolling around to close the chapter out (as if one’s artistic and spiritual visions can interpret the life of another in different ways). Fast forward to how Andrei Rublev finishes, and you have only images of iconography: the sole colour photography in a film that’s black and white, as to not limit the beauty of the art that Tarkovsky vowed to replicate with his own films.

The ending of Andrei Rublev is in brilliant colour, contrasting against the entire rest of the picture.

Rublev’s life itself is tossed in between both symbolic bookends, and even then Tarkovsky grants him the ability to be represented as a saint in life, and not only after death. It goes without saying that much of the film isn’t really about the actual events that happened to Andrei Rublev, but more or less the state of Russia inhabiting these people of different beliefs. Of course, Tarkovsky was always one to unite varying philosophies and ideologies together in the kinds of harmonious ways that only he could, and it was clear that he was capable of this as early as this second feature of his. Comparing Rublev’s internal quests for achieving his salvation against a very complex backdrop is telling: is this how Tarkovsky felt amidst the harshest of Soviet filmmakers’ creations?

Each part “resolves”, but that doesn’t mean they have complete resolutions. Rather, they all still serve the overall story of Andrei Rublev as a whole, as if all of these separate compartments cannot be removed, or else Tarkovsky’s depiction of his life will crumble. It’s actually mightily strange how unlike anthologies or compilation films Andrei Rublev is, despite essentially being one. As if it ran like a from-A-to-B tale, Andrei Rublev is still so uniform that it feels like you’ve watched one large tale (with occasional abstract moments), as opposed to miniature stories. It really is a distinctive cinematic experience in this way, and it perfectly captures the essence of reading scripture (in this case, likely the Bible, I’d say), where one never feels as though they aren’t a part of something much bigger once they finish each page or passage.

The film carries a lot of symbolic imagery, which paints it as clearly a spiritual journey.

Andrei Tarkovsky would never return to this blatant level of religiousness in his pictures again, even though every film would flirt with his spirituality on varying levels. It’s as if Andrei Rublev was his first shot at replicating his faith on screen, he made it count, and realized he was able to move on from this place of his creative consciousness. It’s difficult — nay, impossible — to select just one film of Tarkovsky’s that’s definitively his opus without being strictly subjective about the reasoning behind one’s choice. He has the rare achievement of a perfect filmography. Needless to say, Andrei Rublev certainly has enough going for it that it can arguably be considered his masterpiece, and I couldn’t fault you for selecting it; it’s one of my favourites of his as well.

It’s one of his more literary efforts, and it still contains his knack for capturing the air that connects all of us, rather than profiling the human experience outright. It’s like Tarkovsky leaves a space for spirits or God Himself in all of his pictures, except this time he wanted to chat with Him upfront. Tarkovsky is also aware of the ability to reach anyone’s soulful side, so his meditative filmmaking embraces all. Andrei Rublev is strictly Christian, but it’s a euphoric and life changing experience for any viewer.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.