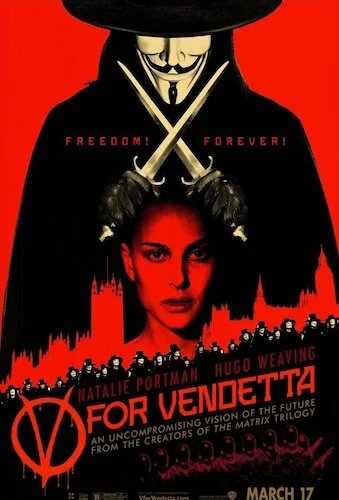

V for Vendetta

Remember, remember, the fifth of November, and the Guy Fawkes plot

For we are reviewing V for Vendetta: a film society’s forgotten, not.

It’s that time of year! Put on your Guy Fawkes masks, get glued to your computer and stream V for Vendetta! Well, actually I could have been alluding to online social activism, or some sort of Anonymous cultism, because the visage has now gone a long way, even veering off course from its original intention. No. We’re not going to be doing anything like that. Today, I’m doing a quick revisit of James McTeigue’s V for Vendetta, which also was a bit off path of what original creators Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s story was trying to convey (although the film definitely captures the latter’s art style extremely well). The McTeigue version (and, I suppose, the Wachowskis, who wrote the story and act as producers, but were originally erroneously labeled as the masterminds behind the entire film back when promotional matter was much more misleading) leaves enough content of the original out that it develops somewhat of a main objective, and not necessarily the one that the graphic novel carried.

Instead of being a rebellion against iron fisted fascism, the film version is now liberal propaganda, which clearly wasn’t Moore’s doings but that of the Wachowskis. I don’t care what political alignment a film carries unless it reeks of hate speech, problematic teachings or flat out lies, but some of the vicious oomph of the graphic novel gets thrown out as well. Despite being a film involving terrorism, 1984-esque control, and torture as a means of cleansing (a complex plot point in and of itself), V for Vendetta kind of strolls along from the first explosive scene right until the final showdown (which is flashy, but not quite the payoff the film deserves either). Even though the production for the entire feature is stellar, the motivations of both story and pacing feel a little confused; you can’t even blame the film for prioritizing action either, because it doesn’t do that either.

The world building — outside of the muddled politics — is a main reason to watch V for Vendetta.

However, not all is bad here. Hugo Weaving steals the entire film as “V”, and at least that character carries enough of the film’s weight for that to matter so much. Weaving is impossible to turn away from, even with his face hidden for the entire flick. The world made here is so thorough as well, so the futuristic London looms more than maybe the characters within the city do. The discussions might run circles or scream louder than the words being said, but they’re still acted with enough emphasis to be exciting (for a second or two). The infusion of Orwellian fears makes V for Vendetta identifiable, but it can also make some of the other plot points somewhat perplexing (the subplot of Evey’s “trial”, let’s call it, seems borderline pointless in this film version, outside of overwhelming feelings). I wouldn’t rely too heavily on V for Vendetta for scratching any political cinema itches, if you’re really into that kind of subject matter. However, if you want some enticing visuals and sleek production, V for Vendetta is at least an entry way film for that kind of fare. It doesn’t compare with the better political flicks, but it holds its own enough as visual entertainment.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.