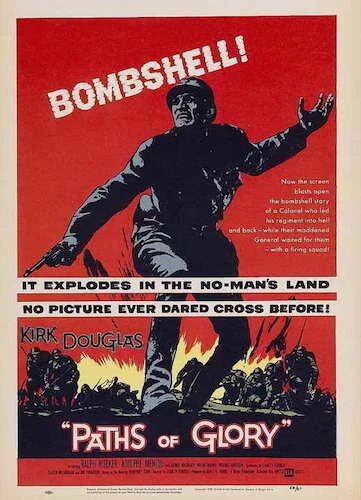

Paths of Glory

For both Veterans Day and Remembrance Day, we’re going to look at one of the finest films about World War I: Paths of Glory.

Stanley Kubrick is known as one of cinema’s most identifiable auteurs, with a style that has been ripped off time and time again. It’s bizarre to think that his vision started at some point in his filmography, and it wasn’t at the very start of it. Sure, The Killing was the first noteworthy film Kubrick made (a great send off to the noir genre), but Paths of Glory is the Kubrick we all know and love through and through (well, aside from the short running time, maybe). Looking at the other works of his that have even any remote connection to war (Dr. Strangelove, Full Metal Jacket, and, to an extent, Barry Lyndon), it’s apparent that Kubrick held a very anti-war stance, as he circled around the lives of those that battled, and how their lives were negatively effected (by universal calamity, the loss of sanity, and much more).

Paths of Glory was made well after World War II, and it was based on the first World War; it was clearly meant to represent both events under one cinematic umbrella. The plot can be applied to any war: a troop is sent in to what is apparently a suicide mission, and they are disparaged for standing down. This leads to a court-martialled trial, where the act of duty goes head-to-head against the protection of one’s self in a blatantly futile attack. Kubrick frames the film to support the side that says that going into what is obviously a losing battle — resulting in many casualties — is morally unjust, but that won’t protect the players that are caught up in this legal debacle.

Paths of Glory takes an anti-war stance, whilst being in support of those who do wish to fight.

I’ve always found it strange that people have willingly claimed that Kubrick didn’t know how to shoot emotions on screen, particularly because it is far from true; maybe if their only points of reference are Eyes Wide Shut and The Shining, this might seem to be the case. Paths of Glory is a greatly empathetic film, regardless of its anti-war stance; it still understands why people choose to fight for their country. No one is made to look terrible for enlisting in Paths of Glory. Kubrick’s main point is that people shouldn’t be used as bait or fodder, even if they have agreed to risk their lives to protect the freedoms of others. That’s the ticket with Paths of Glory, and why it resonates so well within the war genre, and with audiences of all sorts. It takes a moral stance, not a political one.

Because of this, we get some of Kubrick’s most beautiful filmmaking. This includes huge heaps of tension (particularly on the battlefield to start this whole affair off), in the courtroom (with grandiose speeches), and on the floors of the military prison (where hearts open up). All of this leads to the gut wrenching grand finale: a one-two punch of agony and conflicted beauty. Again, I must ask how anyone is capable of questioning whether or not Kubrick could make an emotional film, because Paths of Glory is only emotional. All of the decisions made — including on the battlefield — are purely created viscerally. It’s one of the most exquisite war films I’ve ever seen, and it is borderline impossible to hold back tears (I dare you to try). I can only assume Kubrick naysayers have not yet seen this film.

Paths of Glory is impeccably shot, especially for its time.

I can’t assume that people forget that Kubrick made this, because, again, his thumbprint is all over this thing. For the first time in his career, the nine-zone-grid shots that elongate sets into the horizon are present. The astonishing cinematography (visible ceilings, extreme close ups, obscure angles and all) is all here, and it turns Paths of Glory from legal drama into cinematic art. Of course, this could be attributed to George Krause’s direction of the film’s photography, but we all know that Kubrick had a huge say in how his films looked (after all, he was a photographer first). Either way, the duo pull off a brilliantly shot film that makes the court-martial never ending, fear impossible to ignore on the faces of the accused, and shadows the life force of looming dread.

All of these aesthetics magnify the internal conflicts of every character, whether they project confidence or panic. It’s as if the fighting has been taken off the battlefield and slapped down into the middle of a courtroom for all to see. Words fly instead of bullets here. We get a chance to truly get to know the men that fought for their nation at any point, but here it’s specifically the first World War smack dab in the middle of a trench. How could they be accused of cowardice, when they have obeyed every command up until this point willingly, in the name of freedom? That’s the kind of injustice Kubrick aimed to highlight, and he manages to hone in on it in each and every single frame. As stunning as the film is, borderline every shot is a reminder of power imbalances (bodies towering over others), discomfort (wide angled lenses), and scrutiny (extreme depths of focus).

The complexities of war are heated to a boiling point in Paths of Glory.

Paths of Glory proves that we all choose different ways to honour our country, and that even spreads out into different ways to fight for said country. People that are willing to risk their lives shouldn’t be punished for backing out of a suicide mission that values them as worthless; they might be willing to die, but not as arbitrary diversions. All of these differing viewpoints clash together in Paths of Glory, and it can be a lot to take in; can we even see the arguments of the opposition, especially when the trial is biased and without a stenographer to record the goings on? Clearly, Paths of Glory does take sides in this particular matter, but I’m willing to bet most viewers would take the same side, if not all. After all, if it’s lives that war is meant to protect, then it makes sense to protect those fighting for that safety, and not sending them out purposefully to get killed. It’s something Stanley Kubrick definitely felt strongly about, and his heart is stretched all over the entire picture. Perhaps it was from this point on that he could see what he was capable of, but Paths of Glory was the first true masterpiece that Kubrick created, and it all stemmed from his call to humanizing the soldiers that serve for everyone; even those against fighting.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.