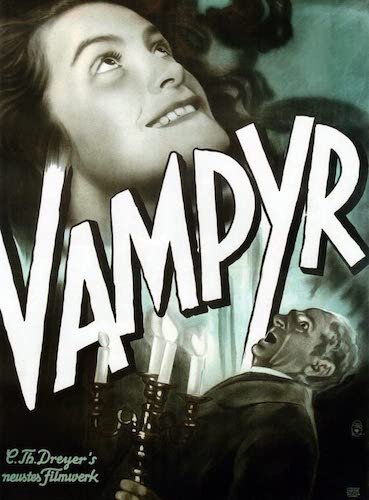

Vampyr: 31 Days of Horror

For all of October, we will review horror films. Submit your requests here, and you may see your picks selected!

The Passion of Joan of Arc was a revolutionary film during the final days of the silent era, but Carl Theodor Dreyer took the success of his biographical picture to heart. He wanted to make less films (he was arguably prolific during the ‘20s), and make each individual picture perfect. Well, I don’t think he wanted to slow down quite as much as he did, considering the Danish film industry didn’t get quite the breakthrough that other nations’ production companies managed to. His filmography was throttled to one film a decade until his death, but what a run that was. Ending with the glacially blissful Gertrud in 1964, Dreyer’s filmography also contained the philosophical Ordet and the heart wrenching Day of Wrath. Before this run of gradual brilliance started, the previous series of hit-after-hit had to end, and it did so with Vampyr. As Dreyer’s first sound film, Vampyr was his opportunity to really experiment like he never had before.

There’s a reason why his other works of excellence, including all that I have named above, haven’t been as aesthetically adventurous (outside of Gertrud, maybe) as Vampyr, and it’s simply because Dreyer reached the peak of his aesthetic storytelling capabilities with this surreal gothic tale of demise and soullessness. Every single sequence is a feast for the eyes, and a daring slice of storytelling bursting to be told. Even nearly ninety years later, Vampyr is a horror film unlike any before or after. It is a perfect harmonization of choppy silent frame rates, sound exploration, and inter-title text versus speech. In the way that Luis Buñuel was exploring with L’Age d’Or and surrealism, Vampyr smushed the end of an era with the innovations of tomorrow into one cinematic classic. Vampyr was made at the right time and by the right imaginative mind.

Vampyr uses shadows creatively, especially considering how well they soak up an image on film.

If Joan of Arc was Dreyer’s discovery of the close up, then Vampyr was his channeling of shadows, even long before films noir or Orson Welles, Jean-Pierre Melville and company could get a hold of them. If anything, shadows don’t even drench every shot like some of the aforementioned works and filmmakers did. Objects, beings, and indescribable images loom over characters and sets, as shadows overtake as observers. These can be used symbolically (see the above shot, with an eerie scythe), or abstractly, with the obstruction of a scene’s sanity being created by images the viewer has to interpret. Even when Vampyr is a little more reserved, shadows are used to create uneasiness, long before it becomes chaotic.

It also doesn’t take long for Vampyr to show its true shades. With a brief runtime of an hour and ten minutes, this feature delivers many horrific moments rather early, and revels in a gothic-dreamy matrimony. The film doesn’t really try to blur lines too much, as you are aware of what is actually happening and what isn’t, but there is enough toying around that Vampyr becomes at least somewhat of a guessing game. How much of the film can we really trust? Well, without giving too much away, Vampyr answers that in a way you might not like (unless you’re a sadistic horror junkie, which, let’s be honest, you likely are if you’re reading this). Spooky doesn’t even begin to describe Vampyr, as Dreyer was willing to go beyond many peoples’ spiritual thresholds at the time. Vampyr is just downright frightening.

Much of Vampyr is uncomfortable to watch, even today. Without being even remotely gory, the film still manages to get under your skin.

Some films just have elements they can’t even control in their favour, and Vampyr has time on its side. Sure, it bested the test of time, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Old horror gems contain an indescribable, uncanny discomfort that just can’t be achieved nowadays (unless a film, like Begotten, tries to mimic it). The bouncing frame rates (between 24 and much less than 24 frames per second) are part of the appeal, but it’s the latter that really makes it for me. Horror images like this feel otherworldly, unobtainable, and just that much freakier, as if their inorganic state renders them unstoppable. In some instances, this aging actually cheapens content and effects. Not with Dreyer’s possessive vision. I’d argue that it has actually sharpened the content even more as it gets older. We’re at such a distance from films like this now.

After all is said and done, we still have yet to even discuss Vampyr’s greatest strengths, and those are the countless other effects Dreyer indulged in here, including overlays, panning, obscure shots, and more. All of this is used to create a frantic mind overloaded with fear, when dealing with the titular “vampyrs”. A romantic tale disrupted by monstrosities, Vampyr is secretly a hopeful tale, meant to go the distance with love. It can be hard to see it this way, when there are so many unforgettable experiments here (especially during the rise of experimental, underground cinema). The occasional moments of peace do drive this point home, particularly an almost golden conclusion that leaps off the screen: a contrast against the other terrifying sequences that pull you in.

Vampyr also occasionally involves moments of peace, which greatly contrast the rest of the film.

In Carl Theodor Dreyer’s filmography — and in cinema as a whole — Vampyr stands out as a work of its own nature. Dreyer’s works before and after worked more slowly, enjoying the spaces within. Not the claustrophobic Vampyr, where every moment is a strangulation of the senses. The late ‘20s and early ‘30s were a playground for auteurs to bridge two different times of cinematic history, but who really knew how to make the most of these times? Do you continue to refine silent films like Charlie Chaplin did throughout the ‘30s, or do you go full speed ahead like many other directors chose to (Alfred Hitchcock, for instance)?

Only a handful of visionaries were patient, and wanted to amalgamate both ends of cinema’s times in history. Dreyer ended up making an untouchable horror, which doesn’t even feel dated like other groundbreaking works. By refining silent cinema and going against the grain of talkies, he made a horror full of untouchable soundscapes and songs, overwhelming images, and a story that was hinged on feelings more than discussions. He made one of horror’s finest achievements, as if it was effortless. He wasn’t just ready to explore talkies. He was already cemented as a game-changer of cinema for good.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.