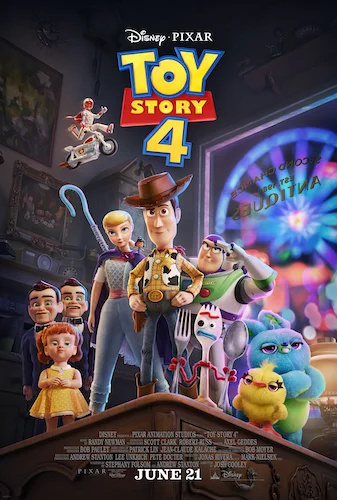

Toy Story 4

A short while ago, I posed the idea that a fourth Toy Story film may not be the worst idea after all. It made little sense at first, because Toy Story 3 ended so emotionally. What can be more powerful than an adult finally letting go of their childhood (when it comes to toy related films, anyway)? Well, the many months of waiting have finally drawn to a close. After leaving the cinema, I concluded that this decade (the ‘10s of the 21st century) is the era of the victory lap: a piece of closure that is one last hurrah, rather than the actual feeling of finality. Kendrick Lamar’s album Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City has a closing track that doesn’t quite finish the concept’s story, as much as it acts almost like a credit sequence: the oomph to stick in your head once you finish an experience. While I can spend all day thinking of more examples (with albums, shows, and films), just know that Toy Story 4 is both a final farewell (in what seems to be for good this time, actually) and one last adventure with the gang. It lacks the emotional roller coaster of 3, but it also dares to ask the questions the entire series has not:

Why are we toys?

Woody starts off neglected in Bonnie’s closet, as his new kid finds joy in other toys. As we know by now, Woody never gives up. He knows his purpose in life: bring happiness to your owner. We get the feeling that the other toys have had to deal with this a number of times already, as their response is not of shock, but of annoyance. Woody cannot give up being important. It’s the inner deputy in him. We’ve seen the entire trek from his perspective, if you think about it. 1 was about him being replaced as the favourite toy, with Buzz Lightyear occupying Andy’s room as the new leader (a new age astronaut replacing the golden years western sheriff). In 2, we find out Woody is a part of a collection, and he was a piece of more than he ever acknowledged. In 3, as disturbing as it is, Woody faced death, and a life without freedom. Toy Story is about playthings coming to life for children, but it’s a hugely existential series for adults.

Woody trying to integrate Forky into the friend group.

SPOILERS

It’s only natural that Woody begins to wonder what all of this is for. He finds abandoned toys in the Second Chance antique store (including Bo Peep: a toy that belonged to Molly [Andy’s sister]). He also sees toys that are given away as prizes at a local carnival. Finally, he stumbles upon toys that flat out do not have any specific purpose: Bo Peep is now one of them. The film begins with a look back at the night Bo Peep was given away (since we do not see her in 3 at all: that void had to be filled). The film actually begins extremely quickly with this sequence, without any seconds to spare. I actually thought this was a beginning short (my screening didn’t have any, if there was meant to be one), but it was actually the film. I guess there’s no need to establish an environment anymore. It’s part 4. We know why we’re here. We just need to know what 4 is all about, so no time is wasted.

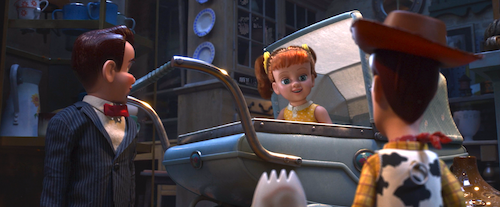

Having the doll Gabby Gabby start off villainous, only to turn into a toy that just felt left out and wanting to feel warmth, was a nice touch, because it works as a tether point for Woody himself. It’s a bit strange to have a Toy Story film without an explicit villain, because there has always been at least one. I guess Woody realizing he has been fighting himself the entire time is the ticket, and that may have all been lost had he needed to fight someone else this whole time. We get a noble sacrifice (Woody giving up his voice box for Gabby Gabby, so she can no longer be defective), and it’s a moment that hurts a little bit. We’ve known Woody for over 20 years. Seeing him incomplete is kind of rough, to be honest.

That’s why his new life at the end of the film works. Bonnie may never love Woody as much as Andy does. Woody has found solace with toys of new, and of old (Bo Peep). What I also love, is how this longing isn’t thrown in your face. It’s a realization we have as soon as Woody has it. It’s one that comes from Buzz, who twenty years ago was telling Woody to shove it so he can claim top respects. Now, it’s Buzz telling Woody his work is done, and it’s time to rest. We thought we saw the true ending before, when Andy gave away his toys to Bonnie. But, this was never Andy’s story. This was a toy’s story. Woody no longer has to fulfill the joys of a child. He no longer has to fight to be one’s favourite deputy. He is now defective, and likely can’t be accepted by a new child. If there was a moment that made Toy Story 4 worth it, and pushed it up to a 4.5 out of 5, it was this one: the necessary statement in a series many of us have grown up with.

END OF SPOILERS

Woody finding Bo Peep.

As a whole, Toy Story 4 is the usual stuff we’re getting from Pixar nowadays, especially in sequel form. Outside of the parts that really kick it up a notch (found in the spoiler section), it’s as surface level as Finding Dory, for instance. Toy Story 4 excels past these films, because of the little things. There are a number of heart wrenching moments created by the emotionless face of a toy, and it’s a power that only Toy Story can muster. Maybe it’s the history with these films. Maybe it’s just how well the concept of toys coming to life works. Either way, you will feel like you are watching some of these other Pixar sequels, but I never came to the conclusion that this film was aiming low.

We do get the same lost toys shenanigans we’ve had three times before, but it feels just as necessary in 4. We start off with Forky (a spork turned into a toy through crafting) knowing his place is in the trash can (as he was discovered in the garbage). Sporky runs off, and Woody tries to save the day again. Instead of a straight forward (kind of) route back to safety, Woody basically has his life flash before his eyes. The actual rescue and journey is the most conventional in all of the Toy Story series, because we’ve seen this three times before. It’s who Woody bumps into on the way that counts.

Gabby Gabby being introduced.

We know toys can be assembled from anything. We learned that through Sid. We know toys an exceed beyond being an activity for children. Al taught us that. We know toys can be misused. Lots-o’ was a little heavy handed with that notion. What we needed is to actually experience the non-villainous side of all of this, and Toy Story 4 is a connective finale that wraps all of this up in a way we didn’t think we needed. It isn’t the spark of imagination 1 was, the thrill ride 2 was, or the emotional whirlwind 3 was. It’s its own film: a bit of all-of-the-above (which all of the films are in their own way), but also a lingering thought finally being addressed.

At this point, I officially do not think Pixar nor Disney can go anywhere from here. All of the avenues living toys can venture through have been explored. We’ve witnessed all of the human connections, too. With a wink towards how the story all started (as well as the usual Pixar easter eggs, including a living Tin Toy from the original short of the same name), Toy Story 4 ends in a way that insinuates completion. The roads ahead are fully addressed, so we know the adventures will never end. Yet, this may be the end for us.

If that is the case, Toy Story 4 has helped the series fulfill the unthinkable. Toy Story was never intended on being more than one film. It then became a great modern two-punch with 2. It then became one of the great modern mainstream trilogies once 3 came out. Now with a very solid, fun, and even impactful 4, we have a great series without any blatant blemishes. Unlike most trilogies or series, Toy Story was never planned. Each subsequent film is a gamble. We have never seen the likes of anything like it in mainstream cinema, yet here we are. I wouldn’t insist that Toy Story 4 is the best of the series, because it isn’t. What it is, though, is a very worthy tale that fits right in, feels as though it should belong, and operates as the actual goodbye that we forgot we even needed to have. It took twenty years, but “To infinity, and beyond” went from being a nonsensical catchphrase from an overzealous toy, to being the many possibilities that could be had in our minds after an animated achievement of a series finally winds down (so we think).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.