3 Women: On-This-Day Thursday Review

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For April 3rd, we are going to have a look at 3 Women.

Robert Altman either refined the rules of cinema, or he broke them. Nashville, The Player, and Gosford Park understood narratives and characters way more than you would assume on paper. McCabe & Mrs. Miller loved to sing a different tune. If anything, Atlman was so clever, he basically set precedents well before Steven Soderbergh and Robert Rodriguez attempted to bounce between the mainstream and the arthouse.

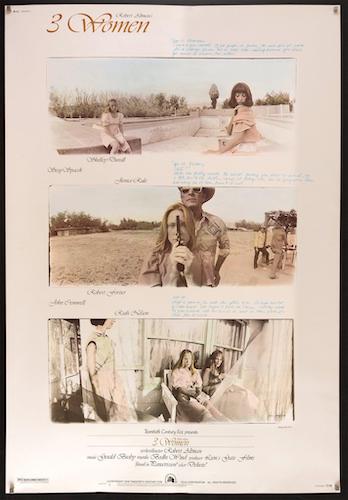

3 Women was a successful attempt to strip the rug from underneath you entirely. This film came out two years after Nashville, mind you. After major awards season success, start studded casts and all of the eyes of the world on him, Altman went deceptively humble. Here was a simpler film. Sissy Spacek, Shelley Duvall, and a very small appearance by Janice Rule. Things were looking quaint.

You reach the end and have long-since realized that this was Altman's passionate tribute to Ingmar Bergman's Persona: an American rendition that featured desert rubble instead of an island, a roommate instead of a patient, and an outside force instead of our mind. Willie (Rule) spends the entire film piecing together mosaics. She is quiet but she understands it all much better than we do. We live through fragments, between reality, dreams, space and time. There are three women, there are two women, there are six, and there is one. There is no official correct answer. Altman just wanted you to at least pay attention to three to get the gist of it.

Pinky and Millie in an early scene.

Millie tends to Pinky as a gracious host, only to seemingly be talking to walls for most of the film. We think she is naive at first; halfway through, we're not sure what to think at all. 3 Women favours the flipping of characters, the death of a cohesive narrative, and the removal of certainty. We see pool artworks and tanks containing fish. We, too, are beings that swim and encounter each other, through near misses and collisions. This film celebrates both: the absence of what-may-have-been, and the changes in fate when something does exist.

Water makes for a great thematic element, but it enforces Altman's desire to represent the dream world, too. So does the sleep-enduring lavender lace that is cloaked on every single image. Like a faded film stock, the images play like a distant memory; one we never had but still somehow connect with. When our mind starts playing tricks on us, it's an automatic betrayal. One by one, your thoughts get cut in half. Nothing makes sense. How could the guy that made Nashville do this to us?

A scene where Pinky has gotten more comfortable with her surroundings.

In case you haven't noticed, I am deliberately avoiding going deeply into the story. If you have not seen 3 Women, it is best to take it all in with as little knowledge about it as possible. Expectations ruin the fleeting experience of you chasing after the bus just when you thought you arrived at the right time. Despite the fact that a basic storyline is mostly abandoned here, 3 Women still toys with literary symbols, dialogue cues and character purposes. That is part of the fun: watching it all dismantle like a house on fire. This house is reality. This house is film.

The ultimate unofficial trilogy (created by me) is the Persona trilogy, consisting of Persona, 3 Women, and Mulholland Drive (by David Lynch). Persona is the death of an awake mind. Mulholland Drive is a catharsis in the subconscious dream. 3 Women is an in between bridge: a tip-toe through a day dream. Everything is presented as tangible, even when none of it makes sense. Much of it is horrific. Some of it is pleasant. This confusion of identity and solidarity has been seen before (and since), but not quite like this. There is no Hollywood glitz and glamour. There is no Scandinavian island getaway. There is only the dust in the air, the dirt on your feet, and all of the specks being glued together in between. 3 Women is a pile of sand that remained, was picked up, and planted back down scrambled. Your brain makes sense of it all, in it's own way. The only familiarity here is time, and its damnation it bestows upon us, even when everything is shaken up.

Millie and Pinky with some of Willie’s art.

That is the scariest moment with the film. It all hurts, even when it becomes foreign to us.

Persona creates the panic. Mulholland Drive establishes the demise. 3 Women is of it's own nature: it is the actual slipping away. It feels much more fluid than Persona's sharp cuts, and more distant than Mulholland Drive's deep aesthetics. Most of 3 Women can be described as a haze, and it becomes a test to identify when everything comes crashing down. Robert Altman knew how the broken pieces of a film would land, and he knew how to put it back together through spacial displacement. The shape is retained, but the foundation is unorthodox. 3 Women is a testament to the cinematic language being bastardized for the world to witness: right when Altman was hitting the big time. What a beautiful, frightening lesson for the casual movie goers of the world back in 1977.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.