A Devoted Misconception: The Difference Between Religious and Faith Films.

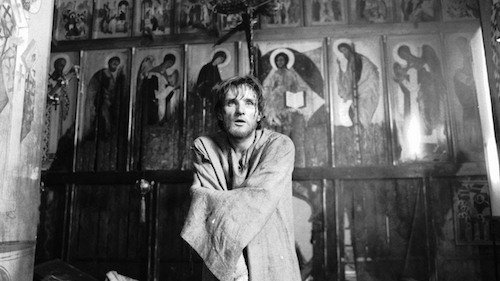

Andrei Rublev; one of the sensational religious films.

Faith based filmmaking has its own little following made up of devoted religious believers (mainly Christian, of varying denominations). These films almost never do well critically. This has given religious filmmaking a pretty bad reputation. There is, however, a very clear difference between faith films and religious films. This understanding explains all that you need to know when it comes to making your choices (depending on your preference). Faith based films are made by Christians, for Christians, and they follow a very particular mold. Religious films are made by believers for whoever wants to watch the final product.

You can think of any example (safe or radical) when it comes to faith films. Heaven is For Real. God's Not Dead. Letters to God. These are all pretty different films (especially the borderline insane God's Not Dead series), but they all feel so similar in every way: presentation, production, tone. Sure, some films are more optimistic than others, but this is clearly a recipe that can result in differing dishes. The majority of these films do not do well with critics, yet they may have a bigger audience reception (even outside of the Christian community). This is because these films have one of the strictest demographics out there. Like a concerned diet, not much can deviate for these studios and filmmakers.

A religious student debates an atheist teacher in God’s Not Dead.

This is because religious films can upset entire communities with their artistic interpretations. We've seen it time and time again. A recent example (Darren Arknofsky's Noah) connects a biblical tale with mental illness, political discussions, and fantasy elements (fallen angels that look like they came out of a Tolkien film). Noah was a decent effort that showed some interesting initiatives. It holds a very bad reputation because of its creative deviations. Is the divide beginning to make more sense?

Faith based films are driven by one idea: faith. Duh. These films cannot waver when it comes to evangelical devotion, because viewers put these works on to understand their own beliefs a little bit more strongly. Seeing Noah walk alongside mud monsters -- while technically in the bible (if you see these beings as fallen angels)-- is an out-there concept that bashes a strong identity a devout Christian may have. There can be cinema. There cannot be interpretation.

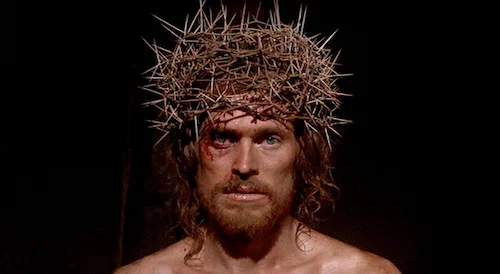

Willem Dafoe as Jesus Christ in The Last Temptation of Christ.

That's where we reach the often-deemed blasphemous The Last Temptation of Christ: a Jesus Christ film that stands out amongst the rest due to its highly different nature. Most Jesus films show the prophet's final days alive, and his resurrection three days later. The Last Temptation treats Jesus as the human form of God, which he was. The film tries to understand Jesus as a human driven by the kinds of sins humans indulged in. This includes lust and anger. Having Jesus wish to live a happy life and be free of constrictions was an artistic liberty meant to tell the story in a new way. He reverts back to God's initial plan, understands he has to die for humanity, and is brought back to the day of his crucifixion to do it all over again.

Now, I can see why this film is deeply upsetting to many religious viewers. The implication that Jesus would engage in sexual and selfish activities, even in a fictitious telling, can seem like a direct attack on a figure many survive each day by. Whether you are religious or not (or are a follower of a different faith), this has to be understandable to some degree. People cling on to something for hope, healing and joy. As good as a film may be, any sort of differing interpretation (especially such a taboo insinuation) can cause a ruckus. And it did. The Last Temptation of Christ continues to be deemed a controversial film, even though it was made by Catholics (Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader). The source comes from renown Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis; an Orthodox Christian that had a strong faith, but found a disconnect with organized religion. Scorsese and Schrader have made other religious films since, particularly the former's Silence (the murder of Christians in a secular Japan in the 17th century). There is no intention to upset a community, but there is a clear effort to tell a refreshing story. Does creating stirring cinema replace a set-in-stone belief? For the strictly religious, can any story replace their favourite story ever written?

The late Bruno Ganz as a guardian angel in Wings of Desire.

There are obviously films that find a middle ground. A little underground film called Ben-Hur (one of many, including the original silent film iteration) clearly did well with all audiences, as it is heralded a staple of cinema. Eleven Academy Awards. Numerous best-of lists. There clearly isn't much of divide. Could the success here come from the focus on the titular character, more so than the story of Jesus Christ? Many straight-on tales of the Christian figure either get lost in the sea of similar films, or they stick out enough for usually upsetting reasons. The Passion of the Christ (Mel Gibson's take), is the same story on paper, but an epic blood bath with its final result. The intent to create the gravity of the situation is evident, but that may not sit well with a number of viewers.

I find the greatest religious films are ones that don't touch any biblical story, nor do they confine themselves enough to be considered "faith" films. These are works that don't step on any toes (believers of the specified faith, other faiths, or no faith). The use of spirituality and religion becomes a transcendental experience. In all seriousness, some of the greatest beauties in cinema came not from the mind or heart, but from the soul.

Every scene looks like a religious painting in The Color of Pomegranates.

Andrei Tarkovsky did create a stir with his iconographer biopic Andrei Rublev, but that was because his film went against Russian ideologies at the time. Otherwise, it is a lengthy, cleansing, gorgeous film that carries its devotion on its sleeve. Similarly, another Russian filmmaker (Sergei Parajanov) told another true story in his own way with The Color of Pomegranates: an experimental visual poem about the religious Armenian ashugh Sayat-Nova. A much shorter film, this interpretation turns every single shot into a moving icon. Both films saw something new out of Christian iconography. No potential blasphemy here. They end up being two of the most breathtaking films ever created.

There's also a take on the afterlife. Wim Wenders' opus Wings of Desire depicts a world with angels looking over everyone. Some people can be saved. Some cannot. Angels in this film can herald human desires, including the curiosity to know what it is like to be a mortal. This transition is non threatening, but perhaps a soul refreshing sequence that will bring life to even the coldest people, no matter what faith.

An overwhelming post-life paradise in The Tree of Life.

The Tree of Life is a much more recent example, where Terrence Malick's conversations with God become an artistic extravaganza that tries to tie together every emotion one can have. The afterlife sequence remains a defining moment of this decade: an exhilarating rush of witnessing the deceased, everyone you ever loved, and permanent illumination all at once. This is visual cinema at its finest: a flurry of thoughts and ideas that demands you revisit this sensation to understand it a new way each time.

We can look at the many filmmakers that have challenged religion (including their own), but I don't believe there is any point. The main focus here was to establish the stigma that religious films have to be boring, safe, or stale. Faith films don't need to change, because they pertain to a small percentage of people that want them that way. That's fine. For those of you wanting something a little more stimulating, you can either venture towards the more difficult conversations (again, not every believer's cup of tea), or you can dip into some of the greatest art house films to ever be put to screen. At the end of the day, I put great cinema first when it comes to watching a film. That isn't everyone's prerogative. Just know that there never is a certainty when it comes to a topic, theme or genre, and nothing is a finality if you've experienced it once.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.