Twenty of the Greatest Female Directors of All Time

March 8th was International Women’s day, but why use one day to celebrate the breakthroughs of female directors? In fact, many pushes in the evolution of the cinematic language have been through the works of daring women directors. This stems all the way back to even the earliest days of cinema. A list wouldn’t suffice when it comes to detailing all of the important films created by female directors, so I wish to put an emphasis on the fact that this list only includes some of the greatest. Even then, it was difficult picking only twenty; I started off with ten, and even that was just too few. There won’t be a ranking here; instead, each entry will be in chronological order, to bookmark the innovations these directors pulled off. To celebrate women for more than just one day, here are twenty of the greatest female directors of all time.

Alice Guy-Blaché

Some Notable Works: La Fée aux Choux (1896), The Lure (1914) The Vampire (1915)

Wrap your head around this one: film historians claim that Alice Guy-Blaché was virtually the only female filmmaker in the world between 1896 to 1906 (according to official accreditation, and with the assumption that other female filmmakers may have worked under pseudonyms or had their works permanently lost). For ten years, Guy-Blaché and her groundbreaking films were the only works made by a woman in the cinematic world that remain (or even existed at all). This includes her controversial works full of societal commentary (including the positions women were pushed into by male-driven communities), and her urge to push boundaries (editing effects, taboo casting decisions for the time [female leads, interracial partners]). She even started Solax Studios with her husband Herbet Blaché, which was responsible for the film with the first all-African-American cast ever (A Fool and His Money); sadly the studios burned to the ground in 1919.

Lois Weber

Some Notable Works: The Hypocrites (1915), Where Are My Children? (1917), The Angel of Broadway (1927)

Unfortunately, most of Lois Weber’s films are considered lost (impossible to locate, or missing enough parts to be incomplete beyond repair), and the preserved films are archived for further protection. Chances are you may not come across any works of Weber’s before. However, her impact remains intact. Author Anthony Slide has insisted that Weber’s films are as important as D. W. Griffith’s in terms of how they shaped the earliest forms of American cinema. Weber did it all, from directing, producing, screenwriting, and acting; she created hundreds of different works. She broke ground with works that were way ahead of their time, including the involvement of political discussions (abortions, sex) and the very first film to feature full female nudity.

Marian E. Wong

Notable Work: The Curse of Quon Gwon: When the Far East Mingles with the West (1915)

Marian E. Wong (also seen as “Marion”) is here because of her importance to Asian American filmmaking. She created the Mandarin Film Company, which was a breakthrough for Asian American performers and crew members, especially since this company was to help create jobs for such workers. The most significant film made was The Curse of Quon Gwon, which unfortunately failed enough financially to put the company into jeopardy. This film has been found in various pieces over the years, though it is still incomplete enough to be considered lost. It is, however, being treated as a coveted artifact in American filmmaking, because of its rarity and the importance of a figure like Wong who went up against the odds no matter what.

Germaine Dulac

Some Notable Works: La Fête espagnole (1920), The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922), The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928)

We’re already entering experimental and impressionistic territory, but that says a lot when it comes to the legacy of the French film theorist Germaine Dulac. Formerly a fighter for feminist rights through her writings, Dulac began to channel her voice through the art of cinema; the word “art” is used heavily, seeing as Dulac was driven by film’s aesthetic capacities. With creative overlays of shots, distorted images, and heightened subject matters, Dulac knew how to toy with the properties of the cinematic language well before many other directors attempted to shape with film. Many of her films also featured women at the forefront, usually dealing with matters that could be easily linked to the struggles they faced in real life (including sexist oppression).

Dorothy Arzner

Some Notable Works: Manhattan Cocktail (1928), Working Girls (1931), Dance, Girl, Dance (1940)

You might notice a bit of a jump in years between this entry and the next entry. That’s sadly because female directors weren’t being picked up in Hollywood (or they worked under male pseudonyms). One very clear exception was the pivotal Dorothy Arzner, who went against the grain in so many ways. Firstly, she was one of the few filmmakers — female or male — to gracefully transition from the silent era to the dawning of sound pictures. Secondly, she created works in both the pre-code era, and had defiant works during the times that the Hayes Code stymied many Hollywood pictures. She was the first female director of a sound picture, the first woman to join the Director’s Guild of America, and her hiring of a number of female stars helped propel their careers (including Lucile Ball and Katherine Hepburn).

Leni Riefenstahl

Some Notable Works: The Blue Light (1932), Triumph of the Will (1935), Olympia I & II (1938)

Though Leni Riefenstahl’s reputation has been tainted due to her connections to the Nazi party through her films, her technical innovations are absolutely impossible to ignore. Riefenstahl was personally hired because of her cinematic expertise to make pro-Nazi films. Through her propaganda works, she became one of the most important game changers when it came to camera operations. This is especially true with the incredible Olympia: a sports documentary split into two parts. What was meant to be a glorification of Germany’s talents in the 1936 Summer Olympic Games became a permanent fixture in both cinema and television, including slow motion replays, dynamic angles used to capture pure athleticism, and shots played in reverse.

Maya Deren

Some Notable Works: Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), A Study in Choreography for Camera (1943), The Private Life of a Cat (1944)

In the underground cinematic scene, not many names register as much applause as Maya Deren’s. An absolute expert in experimental shorts, Deren was able to instil a dreamlike environment and avant-garde stage that was all but disintegrated at this point (thanks to sanitized Hollywood’s takeover on the world). Artistic expression was a major focal point in Deren’s works, no matter what cost. She often worked with her husband Alexander Hammid (when it came to directing), but she insisted on doing most of the work herself (down to the writing, performing, producing, and even the editing). Meshes of the Afternoon — her most acclaimed work — has been referenced to death at this point (including Janelle Monáe music videos, and Dior advertisements), but that’s just a testament to how hypnotic it truly is (cementing it as one of the all time great cinematic shorts, without question). Now, Deren is a staple in film schools all across the world; it’s too bad she wasn’t as praised during her short life and career, because she deserves all of the appreciation for her untouchable works.

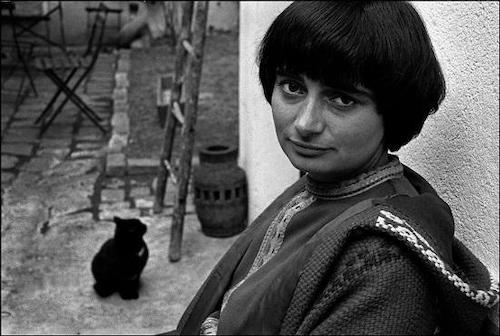

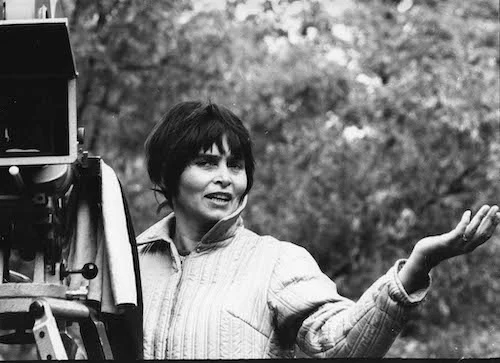

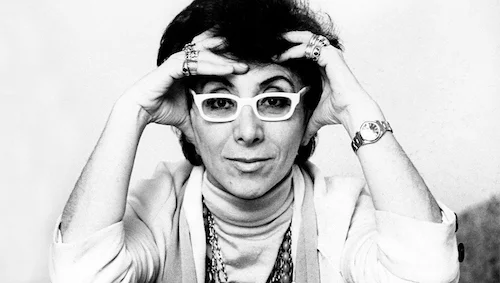

Agnès Varda

Some Notable Works: La Pointe Courte (1955), Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977)

While Maya Deren was not around to see her classics take off, luckily Agnès Varda has been able to see her justified acclaim come full circle. In fact, Varda is still making films, even at the age of 90 (her documentary Faces Places was one of the frontrunners to win Best Documentary Feature at the 2018 Academy Awards). At the start of her career, Varda was cast aside when it came to the labeling of the usual-suspects involved with creating the French New Wave movement (you know, your Godards, Truffauts and such). Now that the movement is seen as such a permanent fixture in the history of cinema, Varda’s works have rightfully been reevaluated, and her crown as the Queen of French New Wave has been created. In fact, her works hold up so well that they are experiencing a rebirth of sorts, including a number of her classics being preserved and released by the Criterion Collection.

Věra Chytilová

Some Notable Works: At The World Cafeteria (1965), Daisies (1966), Calamity (1982)

Just a few paces past France, Věra Chytilová was taking part in her own version of an experimental movement: the Czech New Wave scene. Chytilová’s drastically unorthodox films set a precedent for avant-garde cinema world wide. What she also pulled off, however, was being the figurehead of feminist cinema during the more rebellious moments in film history (when European cinema rebelled against Hollywood’s safeness, and eventually Hollywood followed suit). One signature example is the highly challenging Daisies, which did everything in its power to ignore cinematic conventions, male-driven politics, and artistic semblances. When you hear about the impact of different voices, Chytilová is a prime example of what a different perspective is capable of telling us.

Lina Wertmüller

Some Notable Works: Let’s Talk About Men (1965), Love and Anarchy (1973), Seven Beauties (1975)

On the topic of rebellious films, Lina Wermüller championed the anarchist in her works. She planned to dispel the very idea that society was exactly as it should be. Her quest to question the actual strength of crippling political scenarios started back in the early ‘60s, and continues to this day (her latest film was released in 2004: Too Much Romance…It’s Time for Stuffed Peppers); Wertmüller is still around at the age of 90. Her emphasis on challenging norms, oddly enough, got championed even by the critical masses, even during their actual times. Wermüller was not just a Cannes darling, she ended up becoming the very first female director to ever be nominated for an Academy Award in that category (for Seven Beauties).

Chantal Akerman

Some Notable Works: Hotel Monterey (1972), Jean Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Toute un nuit (1982)

We continue the theme of female filmmakers that went against the very foundations of cinema (perhaps because so much of the industry was determined by men). With that in mind, we arrive at Chantal Akerman’s entry: Akerman may have been one of the boldest filmmakers to have ever taken on the medium. Akerman’s films never hid behind cuts; she adored the use of long takes and still, patient shots. She didn’t allow her subjects to hide behind words, as many of her works involve moments with little dialogue to work with. Her greatest feature, Jean Dielman, began being reevaluated at the end of the century; it is now being recognized as, potentially, the greatest work of feminism in cinema history. Unfortunately, Akerman battled greatly with depression, and it led to her passing away just recently (2015).

Julie Dash

Some Notable Works: Diary of an African Nun (1977), Illusions (1982), Daughters of the Dust (1994)

Julie Dash’s name might sound familiar to you now (and only within the last few years); chances are you stumbled across her name once Beyoncé’s acclaimed Lemonade film was reportedly greatly influenced by Dash’s work (and it shows). That’s no problem, because Dash is one of the most important cinematic voices when it comes to women and persons of colour. Dash has worked with documentaries, shorts, features, you name it. She fought tooth and nail to make statements on how African American women were being depicted in society since the ‘70s; decades later, Daughters of the Dust became the first theatrically released film by an African American female director (in 1994). Dash continued to tell her tales in every medium, and has even made works for television (including The Rosa Parks Story) since.

Jane Campion

Some Notable Works: Sweetie (1989), The Piano (1993), Top of the Lake (2013, 2017)

Another tale of perseverance, Jane Campion worked mostly with shorts, beginning with the film Tissues back in 1980. She finally made her first feature titled Sweetie in 1989, but her best work was just around the corner. The Piano brilliantly creates a mute female lead character, who has no voice (literally and figuratively) over the men in her life (and it contains one of the greatest performances of all time, by Holly Hunter). This film went up against Schindler’s List at the Academy Awards, for crying out loud. Campion was even the first female director to be nominated since Lina Wertmüller, which is way too big of a gap if you ask me). Her aesthetic visions continue to be praised to this day, including her works for television.

Kathryn Bigelow

Some Notable Works: The Loveless (1981), The Hurt Locker (2009), Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

We are reaching the periods when more female directors were being hired by Hollywood, and there is no better person to start with than Kathryn Bigelow. Her first film (The Loveless) was a co-director effort with Monty Montgomery, but her first solo film came shortly afterwards (the cult classic Near Dark). Bigelow was married to director James Cameron for a brief period of time, and continued to work within the Hollywood system. However, there came a new millennium, and we were granted a brand new Bigelow with it. While she experimented with female roles in films, and the ability to twist Hollywood’s expectations on its head, we only saw what she could do later with the heart pounding The Hurt Locker (the first, and sadly only, film to reward a female director a Best Director Academy Award, as she beat out ex-husband Cameron), and the female-driven political thriller Zero Dark Thirty. Now, Bigelow is at an untouchable place in the cinema world, and any subsequent release (including the underrated Detroit) is guaranteed to continue changing socially conscious cinema.

Sally Potter

Some Notable Works: The Gold Diggers (1983), Orlando (1992), Ginger & Rosa (2012)

As Sally Potter experienced filmmaking in the ‘80s and ‘90s, she knew the importance of being a female director was more than just holding that title. For instance, she held the door open on the production of The Gold Diggers to allow for an entirely female crew. Her next feature was similarly daring, and took nine years to come to fruition. Her opus, Orlando, analyzes the shifting tides of feminism, queer culture, and androgyny, through a gender-bending performance by Tilda Swinton (who transforms from male to female over the course of countless decades). Potter continues to make films, and each work continues to battle society’s notions on sexual exploration, no matter what the times are.

Claire Denis

Some Notable Works: Chocolat (1988), Beau Travail (1999), 35 Shots of Rum (2008)

Claire Denis had a conversation on society, and it continues to this day. She utilizes film as a megaphone to discuss the effects of colonialism, societal pressures, and other oppressions that many marginalized communities face to this day. What makes Denis truly special is that she was brilliant from the very beginning. Her first feature Chocolat continues to be a staple in world cinema classes. Beau Travail has been deemed one of the most important works of world cinema of all time. Then there are her many underrated works. Luckily, Denis is still releasing films, and her English language debut (High Life) is due for a North American theatrical release soon. With this recent announcement, Denis will no longer be a part of just the film academic communities; she will finally be known by the entire world, as she so deserves.

Deepa Mehta

Some Notable Works: Sam & Me (1991), Fire (1996), Water (2005)

Deepa Mehta’s name is so recognizable, because she has singlehandedly taken on being the face of so many cinematic communities. She is a powerful female filmmaker. She is one of the most influential Indian filmmakers, regardless of gender. She is also one of the most important Canadian filmmakers. With all of that considered, we still need to discuss the impact of her works. Her acclaimed elemental series (Fire, Earth, Water) showcase serious topic matters that were even ahead of their time, including homosexual relationships in strict environments, children forced to marry, and the struggle between identity and politics. Mehta’s ability to unite so many worlds, and create so many discussions, has rendered her an iconic figure in a number of circles.

Sofia Coppola

Some Notable Works: The Virgin Suicides (1999), Lost in Translation (2003), Marie Antoinette (2006)

It’s interesting to analyze Sofia Coppola, because her work is so idiosyncratic. Some of her works were acclaimed the second they were released. Others, including Marie Antoinette, weren’t as well received, yet it’s as if we are already witnessing their revivals. Despite being the daughter of one of America’s most acclaimed filmmakers (Francis Ford Coppola), Sofia tends to play by her own rules, regardless of how they may seem. In 2019, when perspectives are shifting and works are being reassessed, it’s clear that Coppola had a voice from the very beginning, and many critics may have misunderstood it. Marie Antoinette is now being seen as a strong, anarchistic feminist work that, like the titular royal, didn’t want to play by the rules. Her classics, like Lost in Translation, only get stronger in their own right.

Ava DuVernay

Some Notable Works: This is the Life: How the West was One (2008), Selma (2014), 13th (2016)

Ava DuVernay is one of the current filmmakers that knows how to blur the lines between documentary films, and live action features. Having been fascinated by her ability to communicate societal struggles from the start, DuVernay has delivered shorts, documentary features, and fictional stories that highlight ongoing issues (usually within the African American community and its battles against oppression). Everything came together with the Martin Luther King biographical picture Selma, which put Hollywood in a trance when it first came out. Shortly afterwards was the spellbinding (yet stomach churning) 13th, which depicts the problems with the loophole found in the thirteenth amendment of the constitution (and the ability to use it as a means of finding other ways of creating slave cultures).

Nadine Labaki

Some Notable Works: Caramel (2007), Where Do We Go Now? (2011), Capernaum (2018)

We arrive with the last filmmaker on the list with Nadine Labaki, whose works are powerful enough to shake you to your core. As a Lebanese director and actor, she has made her mark on works that have pointed out the problems in a constricted society. This includes even music videos she has worked on, which has sparked controversy for being sexually liberating. Her features have proven to be festival darlings, particularly Where Do We Go Now? (which was voted by Toronto International Film Festival attendees as the best film of the festival), and Capernaum (which was just up for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Feature).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.