American Beauty

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. American Beauty is the seventy second Best Picture winner at the 1999 Academy Awards.

Seventy two years after the Academy Awards started, I don’t think anyone could have predicted what the final Best Picture winner of the century could have been like. Hell, I doubt anyone in 1990 could have made that guess. American Beauty is an indication of how much American cinema has changed over the years, but it still is extremely out-of-left-field with its awards season dominance at the end of the decade, century, and millennium. We were entering the 2000’s. We were still so technologically naive, as we assumed computers would not know how to usher in the new date, could possibly crash, and lead us into a cyber apocalypse. Y2K never happened, and we may laugh it off, as it was a stupid example of mass hysteria. Yet, how many of us — child or adult — believed something was at stake as soon as the year 2000 hit us?

Maybe that’s because it was the ‘90s. The internet was slowly becoming a communication tool, we were learning more about our species as indoor inhabitants, and “the future” was happening now. American Beauty, although a massive outlier amongst its ‘90s Best Picture peers, had to at least mark the tail end of a series of eras. Don’t worry. The Academy was back to its regularly scheduled programming with Gladiator winning in 2000. For 1999, American Beauty captured the westernized existential dread that plagued people of all genders, ages, sexual orientations, cultures, and more. No matter what your daily problems were, you were one of billions of people fearing imminent death and uselessness every day.

Carolyn admiring one of her roses from the yard.

We follow Lester Burnham’s mid life crisis, as he is stuck in a dead end job (as a magazine executive), with a wife and daughter that don’t love him (they needn’t worry, as he doesn’t seem to love them either). New neighbours move in next door (the Fitts), and everyone on the block has to prepare their positive image in order to sustain the ecosystem of the nuclear suburbia. American Beauty never shies away from the awkward side of the human machine, including incessant needs for sex, self-worth, and joy. The misery that the Burnham family fallow in is toxic for sure, but is it any better than the outward lies that the other families spew (or the hidden issues of the Fitts family)? American Beauty is all about the American: the white picket fence, the loving family, the green yard, and the stable life.

Lester vows for a life of zero responsibility. He chases the career path that is often used as a fear-inducing threat to all adolescents: burger flipping. He splurges his dwindling money on shallow nonsense, but he is beginning to feel joy. His wife Carolyn — a struggling real estate agent — is now the breadwinner, and the pressure rests squarely on her shoulders. Isn’t that interesting? Lester was an executive for a magazine; a printed medium that sells ideas to millions of readers daily. Carolyn sells homes to buyers, and has to convey the perfect image for these living corridors. Both of the Burnham parents may not buy into the stigmas crafted by the ideology of the American dream, but they helped fuel them through their career paths. If you’re not the sucker falling for capitalist lies, you’re the loser helping them get stronger.

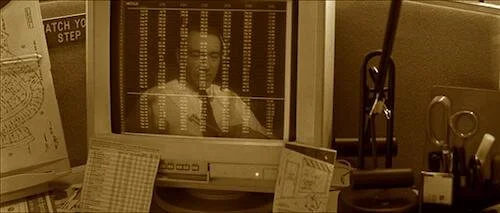

Lester looks like he is in a jail cell, through his reflection on his office computer.

Writer Alan Ball is obsessed with focusing on all of the ugly things that make us human. We feel like we are invading the homes in this neighbourhood, and watching the every move of each citizen. American Beauty is almost voyeuristic, outside of the fact that Lester narrates this film from beyond; in a transcendental airwave. We are given access to the perspectives of all, through Lester’s enlightened spirit. After chasing the fountain of youth, Lester’s futile experiences shed light on the whole. Living entirely consumed by the capitalist machine is no way to live, but doing the complete polar opposite is not ideal either. Life requires a happy medium, in order to maintain an improvement of self. Plants need more than just water to continue thriving. That’s how humans function, too. Work only helps us financially. We also need to take care of our bodies, our minds, and our souls, as well as those that we love (as a means of bonding).

Fitts son Ricky has the right idea, although his methods range from creepy to insane. He finds beauty in everything, including plastic bags floating in the wind. He is not a pervert, because a pretty person to him is just another beautiful creation on Earth; he comes off as the ultimate weirdo, though. That’s kind of his point. His neutral stance on the world, as well as his obsession with all of the gorgeous qualities of life that we miss, stand out. They stand out, because humans have pushed the original starting point of the Earth well past beyond its original state. The planet is unrecognizable as it once was. Forests have been paved for houses. Trees have been chopped for magazines. These goals we permanently chase or sell continue after we die, as if we are a mild inconvenience in the bigger picture of the never ending slog. Someone like Ricky can identify displaced beauty; a tree is still beautiful when turned into paper. A resource extracted from the Earth is still one with its host planet, if it participates in being tossed around by a weather pattern.

Ricky showing his footage of a floating plastic bag with Jane.

The friendship between Jane Burnham and Angela Hayes is tested by toxic culture. Angela must be the hottest girl in school, while Jane wants to disappear entirely (although she wishes to fulfil her own desires, including cosmetic surgery). They drift further apart as the film goes on. Angela capitalizes on Jane’s father’s perversions (the chasing of youth, again), while Jane wants nothing to do with her father (and, in return, her pining friend Angela). We eventually learn Angela was trying to sell her own image, out of fear of never being accepted. She was never too experienced. She wasn’t experienced at all. She felt pressured into being something she is not, just like almost everybody else in this film. This includes Fitts father Colonel Frank, who portrays himself as a hateful war veteran, when really he has been suffering from repression for what could be his entire life. His clashing with Lester is the head-butting of a life tarnished by fear, and a life nullified by apathy.

Frank’s catatonic wife is also removed from the American biosphere, although she is partially aware of what is going on. Her role is small, but it works as an important foil to all. No matter who we look at, everyone is comparable to Barbara Fitts, as she remains sitting in one room for most of her life. Office workers, students, drivers, families at a dinner table. We are permanently fixed to various places every single day, as if we have a choice. We feel sad for Barbara, but Ball is sadistic enough to make you realize how chained we all are with all of our daily habits and necessities. Not all of this work is from Ball, though. Rather late than never, it’s time to discuss how Sam Mendes’ feature length debut is the work of mainstream art. He took Ball’s dark story, and turned it into a contrastive image full of red roses, blue skies, and white fences: the American neighbourhood that suffocates all citizens. Mendes finds a fine-line between warmth and discomfort, and he waltzes across this grey area the entire film. American Beauty feels so humanistic as a result.

Roses are used in both the fantasy and reality segments of American Beauty.

Shot to feel like a dream, and performed to be a painfully obvious rendition of reality, American Beauty is the blurring of desires and end results. In a decade full of romantic epics and crowd pleasers, the Academy somehow pulled off a 180 degree pivot and awarded this peculiar mainstream film with arthouse tendencies the accolade of 1999’s greatest film. Twenty years later, we have found ourselves being obsessed with anything that came out this year (maybe because it scares us how quickly time flies). The Matrix has been shown some recent love. Artists like Charli XCX have created tributes. That era has been recaptured all year in 2019. Awarding American Beauty was like planting a time capsule, waiting for this very moment. Our future selves could look back, and see if the Academy made a bold enough statement awarding this oddball black-comedy-melodrama. If anything, American Beauty speaks more to us now than before. With feuding generations, an internet super connection, and the fear of death being turned into a meme, it’s as if Alan Ball saw what was coming, Sam Mendes crafted Ball’s predictions, and American Beauty knew the American better than we knew ourselves.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.