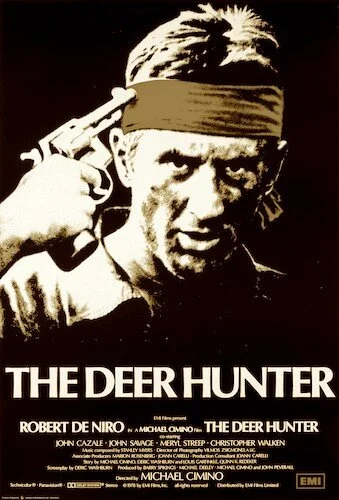

The Deer Hunter

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. The Deer Hunter is the fifty first Best Picture winner at the 1978 Academy Awards.

If you pit Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter up against any other war epic, it just feels strange in comparison. It dominated the 1978 Academy Awards, but maybe that audience wasn’t sure just how alien it felt compared to other anti-war films. Even though Cimino’s follow up film Heaven’s Gate is an even more bizarre film (it was once slammed as an atrocious film, but is now slowly being cherished as a one-of-a-kind experience), it’s a clear indication of just how off-the-map Cimino was. On the surface, The Deer Hunter is extremely straight forward; in fact, a little too straight forward. You see everything, and it’s all nauseating. Deep down, The Deer Hunter was the black sheep of anti-war films: the artsy angle that has not won every viewer over. Almost like a reverse Heaven’s Gate, the attention went from all positive, to being a little more polarizing.

We first have a wedding sequence that makes The Godfather’s opening moments seem like a cakewalk. This one, with the pre-events and the final hunt included, takes up an entire hour. We don’t really learn a hell of a lot, outside of who is taking part in war, what the relationships between partners and friends is like, and what life before war feels like. We take a very long time to get to the actual war. We put up with a lot, including drunken antics, quarrelling, and more. You can view some of these portions as life being wasted, or cherished, before it gets taken away. Once Mike, Nick and Steven leave for war (hence why they are squeezing in marriages and hunting trips as quickly as possible), all will change.

The opening hour is based on celebration attempts, including a wedding and a final hunting trip amongst friends.

The opening third is a tiny bit arthouse in its approach to exposition revelation, character introductions, and scene setting. There are long passages of characters just doing whatever they’re taking part in (drunk or not). There’s not much in terms of non-diegetic influence to shift a scene in any way. It’s almost voyeuristic, how much time we spend watching these people (and within such a close proximity). For a lot of viewers, this is an overlong test of patience. For me, this is a challenge.

How long does it take to get tired of watching this? Once we cross the point of no return, how quickly will we wish for what we once were cursing? On subsequent viewings of The Deer Hunter, I find myself really trying to embrace everything here. It doesn’t last that long at all. A cinematic hour is an eternity, but an hour in life is all but a speck of dust in the grand scheme of things.

One last hunting trip before three of these friends go to fight in Vietnam.

Just like that, the film changes. Boom. We’re right in the middle of the Vietnam War. Mike has a flamethrower, and is battered and bruised. We get zero transition into this segment. That’s how war operates, though. No one is ever truly prepared for it. Just like that, our three protagonists are stuffed into a cell as prisoners of war. They are either tortured, or forced to play Russian roulette. These very lives we spent forever moving away from can now be gone in an instant, and all it takes is luck to determine who can stay. These controversial scenes rank up there as some of the most anxiety inducing I’ve ever seen. Even after many viewings, I still feel like I don’t know what will happen (even though I do). Through the use of actually loaded guns, and real slaps across the faces of various actors, the method acting used in these sequences are beyond extreme.

There has been some disputing about how the Vietnamese soldiers are portrayed here, and I can understand why. I would say that the American soldiers are also painted in a not-so-great light, in exactly the same way. They only seem like the “heroes”, because the film has been following them the entire time, and we view everything from their vantage point. At the end of the day, every character is fending for themselves, and doing so in the ugliest of ways. We see this from one angle. In 2019, this may still cause a bit of a stir, and it’s easy to see how. Having one-sided villains is just a bad writing tactic at the end of the day, but I don’t think anyone in this film behaves in a necessarily outstanding way. It’s just not that kind of film (not for me, anyway).

The Russian roulette scenes remain as dangerous as they ever have been.

The trip back home is a trek in and of itself. Mike, Nick and Steven come back completely different (well, come back being the operative term). The final third is the attempt to repair these three people: Mike emotionally, Steven physically, and Nick mentally (even though each of these three veterans have had crossover effects within the other territories). Absolutely nothing is the same, and no amount of cheer and support can change that. Unlike the opening third, the last two thirds are much more quick moving. Even the moments of solitude in Pennsylvania don’t feel calming at all. Mike, for instance, feels responsible for trying to mend both of his comrades, by being there (or try to be there) for Steven, and by seeking out where Nick is hiding.

The Deer Hunter puts trauma ahead of the war. Even though it’s an anti-war film, Cimino is more interested in the breaking point of people. This titular deer hunter (what an interesting film title for a flick about the Vietnam War) was once so calm and steady, he could hunt animals in one single shot. Now, nothing makes sense. Everything is nerve wracking. Having to hunt people changes the name of the game for Mike; he let his last deer before the war go, perhaps to understand what letting a life be free felt like before he was forced to end many others. The end of Mike’s trek results in complete devastation: the facing of a best friend, and knowing that they were dead long before they were actually deceased. If anything, all three veterans were long gone on the inside.

A group of friends and loved ones, permanently ripped apart by their war experiences.

The Deer Hunter is likely the most unforgiving film the Academy ever crowned Best Picture. The Oscars were definitely warming up towards edgier films, but The Deer Hunter felt like the ultimate turning point. From here on out, many of the subsequent winners would be tamer (even any films with action and gore from here on out). With its content and the frigid natures of the lead characters, The Deer Hunter is easily the coldest film to ever take the top prize. Not only that, it remains a disturbing anti-war effort to this day.

Not many works continue to sustain their love-hate relationship that they develop; this continued until Michael Cimino’s death three years ago. Heaven’s Gate was finally being given a fair shake by many, but The Deer Hunter just kept rustling feathers ever since. It’s junk, or it’s a masterpiece. For me, The Deer Hunter is an existential look at life through the eyes of mentally shattered war veterans. Even the little things in life, that once contained warmth, can be stripped away by hate. Even the beauty of nature can be ended by a hunter with another goal in mind. As uneasy as The Deer Hunter is, it’s a fascinating piece of art covered in all of the horrors created by humanity. It’s nature’s imbalance, and we’re all caught up in it. Life itself is the “one shot” we have, and any single moment can change (or destroy) the remainder of it.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.