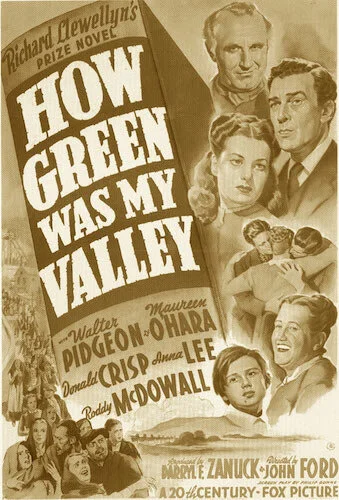

How Green Was My Valley

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. How Green Was My Valley is the fourteenth Best Picture winner at the 1941 Academy Awards.

What a groundbreaking piece of cinema that was left on the doorstep of 1941 America. Camera techniques, make up, acting, directing, absolutely everything was changed. Screenwriting was never so complicated. Contemporary cinematic nuance was finally being fully realized. Yes, Citizen Kane was flawless, and it did not win Best Picture. John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley took home the evening’s biggest prize, and it has faced notorious backlash ever since. Let’s honestly take a step back here for a second. Is it actually Valley’s fault that it won over a now-solidified opus?

Even if we can’t shake off how monumental Citizen Kane is, and how that would be the much more noteworthy film to discuss right here and right now, let’s actually look at Valley for what it is. It’s a stunning film. While flawed, Valley makes perfect sense as to how it could have won. Firstly, Ford was already an established director by the time these Academy Awards came around (he won Best Director twice already for The Informer and The Grapes of Wrath, and would win again for Valley). Despite his multiple wins, his films never won Best Picture until now. I wouldn’t try to convince you that Valley is his best film. It may not even be close to being his best film. However, it’s one of the biggest indicators for how directors like Ingmar Bergman and Clint Eastwood could be influenced by both Ford and this film. Visually, this is completely early Bergman. Conceptually, this screams Eastwood all over it.

Artistically, How Green Was My Valley is beyond rich.

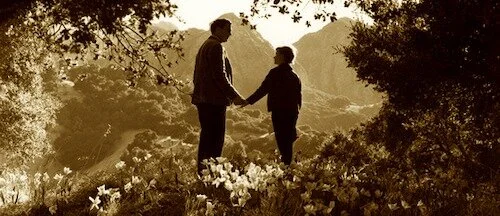

If you look at a number of the shots in this film, it’s easy to see how Valley could win over a whole Academy. Citizen Kane can be marvelled at in retrospect, but I feel like Valley deserves at least some of the same respect. Put the film on, and I can bet that you will be blown away by at least five of the shots. If we’re still comparing Best Picture winners of each era with each other, Valley is probably the strongest black and white winner thus far visually (which excludes Gone With the Wind, of course). On the surface, it doesn’t take much for Valley to hook you in.

Now, here comes the part that took some getting used to for me. Ford loved making films for the everyday American, correct? Even this Welsh tale has some sort of correlation to the American viewers, especially concerning the blue collared struggles of the working class. Well, on the first watch, the film’s puzzling demographic threw me off. Here we have a series of hardships from home, work and school, and a handful of characters that kind of sat on neither side of the good-bad spectrum. As I am used to Ford’s usual blatancy, I read Valley as a conflicted statement that had no real confidence in how it was discussing the classist struggles in Wales (or worldwide).

How Green Was My Valley projects many generational lenses on the same topics, providing differing perspectives on moral debates.

After some time and a second chance, I’ve realized that onus is entirely on me. If Ford can bring a complex character like Tom Joad to life, surely an entire film that feels comfortable not providing answers to every situation shouldn’t be out of the question. That isn’t Ford giving up, either. That’s the wiser way to confront some scenarios. Lord knows life doesn’t have all of the answers for us, and Ford was trying to place all of life in a bottle with this film. With the voices of a mining town all singing at once, it’s occasionally difficult to make sense of every melody. The more I come back to Valley, the better I feel about its handling of all of its dilemmas.

Part of me feels the need to relate Valley to a barely-similar contemporary film that shares just enough common ground: Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. In both works, you endure the combative ways of different parental styles (nature versus nurture), with the gifts of nature and life stringing everything together harmoniously (when civilization cannot work together on good terms, the world around it has to step in). There is much more concrete plot in Valley, as you take part in an abusive education system with the younger generation, the unhealthy coal mines with the older wave, and piece together domestic life with your peers. Many of these worlds intertwine, and not every convergence gets completely resolved. I have come to learn that that is okay.

Much of the film’s imagery is a comparison between nature and human-created infrastructure.

So, go ahead, and join the bandwagon that dismisses How Green Was My Valley because it won. Part of our Best Picture Project is to determine how off the Academy can be sometimes. That shouldn’t make Valley an infamous film. It had zero control over its fate. Did cinema change in any way with Valley winning over Citizen Kane? Absolutely not. You can continue to complain about a decades old decision that had zero repercussions (outside of Kane missing out on awards). All you will be doing is punishing yourself by avoiding a fine film that harms no one in any way. Plus, this is far from the first time the Academy created an upset by awarding a less acclaimed film over a now-established classic. Just soak in all of Valley’s beauty, and you’ll forget about Citizen Kane for at least two hours. It’s a worthy escape, for your soul’s sake.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.