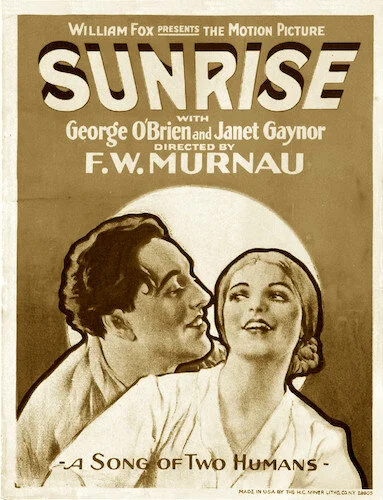

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is the sole winner of the Unique and Artistic Picture category at the first ever Academy Awards.

Okay, time to clear the air here a little bit. The very first Academy Awards actually had two Best Picture winners, although neither of them were actually called “Best Picture” directly. Believe it or not, the Academy back in 1929 (the first ceremony honoured films made in 1927 and 1928) was forward thinking enough (in this particular case) to not only award the best film of the year, but also the best film in terms of artistic merit. This category was called “Unique and Artistic Picture”: the strongest film of the year in terms of creativity and imaginative integrity. The category was eliminated the very next year.

The sole winner of this award is the greatest film by German expressionist visionary F. W. Murnau, titled Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Sunrise on its own works as well). I don’t know where to even begin with this film, outside of stating that its win was more than warranted. Even if you know nothing about silent cinema, taking a single glance at this film (or any of its individual scenes) will explain why this film won such a prize within seconds. Murnau’s opus steps outside of so many comfort zones, especially when it comes to its presentation. The intertitle cards are designed to describe the tonality of each scene, including smokey words, text with effects, and more. This wasn’t the only film to do this, but the way Sunrise presents these particular intertitles is special. You aren’t reading, as much as you are experiencing what’s being written.

“The Man” being manipulated to commit evil.

Then there is the obvious use of sound, during a time when sound in motion pictures was finally hitting the mainstream (don’t give me that nonsense about The Jazz SInger being the first talkie film. It wasn’t, and it deserves zero credit. It’s like Columbus supposedly discovering America. This is a rant for another day). The film still operates as a silent picture, but it incorporates recorded background noise to bring life to scenes. This includes crowds cheering, city sounds, pigs squealing and more. Like the intertitle decisions, these choices brought life to a film that wanted to go about avoiding the tropes of tired films.

So, Sunrise is a love story, but it’s a little bit different than what audiences were familiar with back then. Based on The Excursion to Tilsit by novelist Hermann Sudermann, Sunrise is a more artistic depiction of a severed relationship being mended. Murnau’s interpretation (based on Carl Meyer’s adapted screenplay) is highly metaphorical, despite there being a strong narrative semblance. No one has a depicted name here. Characters include “The Man”, “The Wife”, “The Manicure Girl”, and, the villain of it all, “The Woman from the City” (oh no! Not “The Woman from the City”! Anyone but her!). Basically, this was meant to be a series of tabula rasa archetypes that you could imagine yourself replacing. If you have ever hit rock bottom with your loved one and fought to repair it all, Sunrise was meant to represent this battle.

“The Man” and “The Wife” confronting one another.

So The Man is convinced by The Woman from the City to kill his own wife so they can continue forth as a new couple. The Woman from the City is almost vampiric in nature, with a shadowy grip on The Man (even literally, as her shadow is cast over him, or her image is superimposed onto him at times). This is fitting, seeing as Murnau brought Nosferatu to the world only a few years earlier. The Man — after a few reservations — begins to follow her lead, and commits to murdering his own wife. Seeing The Wife respond (initially with joy, then confusion, then absolute fear) is a heartbreaking moment, and that comes from actress Janet Gaynor’s brilliant performance (she won Best Actress for a few films that year, as the award used to encompass many works of one person each year, rather than one single film).

Much of Sunrise, on a literal level, is the attempt to reconcile a shattered relationship, as The Man chases after The Wife (once he snaps out of his insanity) and begs for forgiveness. This is when Sunrise becomes a magnificent piece of cinematic poetry. We spend time with the two of them, as they try to fall in love again. We get sucked in by the city life: the carnivals, the night life, the joys of the world. By the end of the film, a number of events get repeated, and we inspect how things fare with a different perspective. So does The Man, who had a desire that has now become his greatest fear. The title representing the cyclical nature of the Earth orbiting the sun is very fitting, given that we are experiencing the circles of life with a fresh pair of eyes on the second go around. This includes the second chance at love, the concept of death, and what falling in love feels like to begin with (is it with the person that approaches you at night to demand orders, or the person you can spend your life with?).

The Man and The Wife repairing their relationship through self reflection.

Sunrise was a sensational film when it first came out, and it still feels like a masterwork with how it approaches the exhausted concept of love even over ninety years later. Love has been represented through art for hundreds of years before film came out, but innovators like F. W. Murnau proved that it could be painted differently through this new medium. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans remains one of cinema’s strongest metaphors for love, and the portal for other filmmakers to know what to do with the art form. It’s too bad that this Best Picture award isn’t considered the official winner since the deletion of this nomination category (Wings was chosen instead), since it would have allowed the Academy Awards to have started off with pure perfection in the history books.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.